Do individual competence, integrity, and excuses even matter? We already use structural incentives to get people to do good things they might otherwise choose not to do: economic incentives, legal disincentives, social pressure. If markets, laws, and opinion can squeeze societal usefulness out of groups of selfish individuals why worry about self-centered behavior? Why not just encourage individuals to figure out what they want for themselves and then structure institutions to squeeze social good out of whatever choices they make in aggregate? Let individuals worry about how to get what they want.

The answer seems obvious, at least for social pressure. It is circular to rely on social pressure to police behavior while socially encouraging selfishness. Humans desire acceptance and a feeling of being good which empowers social norms to shape behavior. But if these norms accept excuses and glorify happiness then that is what they will encourage.

While a bit less obvious, civic concern and individual responsibility pull a lot of weight in legal incentives. It is much easier to incentivize people to do the right thing in a community that mostly agrees on the importance of doing right than in one that mostly agrees that everyone should focus on themselves. On what basis should the creators of incentives and enforcers of rules not optimize for themselves otherwise? The difficulty of establishing the rule of law in countries without a sense of civic responsibility should speak for itself.

And while markets might be still less obvious, non-economic concerns with fairness and contribution significantly aid markets. Simple and effective economic incentives are easiest to implement when most believe that good people don’t merely do whatever is most profitable. Consider Deirdre McCloskey’s extensive writings on the importance of values to capitalism, Fukuyama’s Trust on the importance of unselfishness in coordinated endeavors, or simply imagine how different the world would be if most thought it prudent to sneak out of restaurants without paying if they could get away with it.

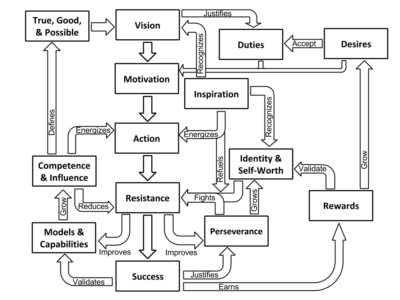

The pragmatic focus on institutions is valuable and necessary, but so is the idealistic focus on the Motivational Compass of individuals. These Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian priorities are in inherent and essential conflict, but one that can be healthy if each sticks to their natural scope. Contemporary encroachment of Hamiltonian values into everyday interactions and beliefs attacks the sense of individual agency and meaningfulness of pride and progress. It questions the honor of competence and integrity. It separates individual actions from larger concerns and mostly leaves hedonistic Last Personhood and cynical battle of interests as the seemingly coherent options.

The basic beliefs that one can contribute more or less, that one can understand how things work better or worse, that these are skills that can be honed, that developing and applying these skills makes one a better person begin to be treated as naive, reductionist, and judgmental. But these beliefs are the essence of mentoring competence and integrity and the fuel that motivates achievement and contribution. Without them people who build, innovate, excel, and uphold principles can only be understood as freaks with an odd set of personal interests and an indifference to their own suffering.